If a giraffe sneezes, does it matter?

“Atchooo” – the giraffe appears somewhat startled by its own sneeze, but then it slowly resumes wrapping its tongue around some leaves high up on an Acacia tree, elegantly avoiding the big thorns guarding its foliage, and pulls the leaves into its mouth, as if nothing ever happened and that sneeze didn’t matter at all.

But does it matter when a wild animal gets sick? In human terms, should this particular giraffe perhaps reach for a face mask and self-isolate for a few days?

We know from ourselves that being sick is not fun, and if that sickness results in death, then that is catastrophic for the individual affected. The same is surely true for wild animals. We hate seeing animals suffer, especially (though not only) if there has been some sort of human involvement in their plight, and so, looking after sick individuals is a very humane, and valuable undertaking. But when does a disease become important not only for the individual, but for the whole species or population?

Wild animals get sick and die all the time. What is important in a balanced ecosystem, is that the number of animals leaving the population are balanced with the number of animals entering the population. If more animals die (or migrate out) than are born (or migrate in), the population decreases in size. Of course the opposite is also true: if more animals of a species are born (or migrate into the area) than die (or migrate away), the population increases in size. This can cause problems of its own, but I’ll leave that for another day (or should I say “post”).

Disease outbreaks have the potential to dramatically increase the number of animals dying, and/or decrease the number of animals being born. This is especially, but not only, true for diseases that are “exotic”, meaning they are new to the population in question. When a population declines, it may become threatened or endangered, and if the trend continues, it may become extinct.

Let’s consider a specific, and rather dramatic, example of wildlife disease.

In May 2015, up to 200,000 Saiga antelopes died over about nine days near their calving grounds in Kazakhstan. They died within a few hours of first showing signs of being unwell. An investigating multi-disciplinary team, including veterinarians and ecologists, concluded that the deaths were most likely caused by bacteria that normally live in the antelope’s body without causing problems, called Pasteurella multocida. Unusually warm and humid weather conditions somehow resulted in the bacteria entering the blood stream of the Saigas, rapidly causing blood poisoning and death.

Saiga antelope (Saiga tatarica) (Image by: Vladimir Yu (Wikimedia Commons))

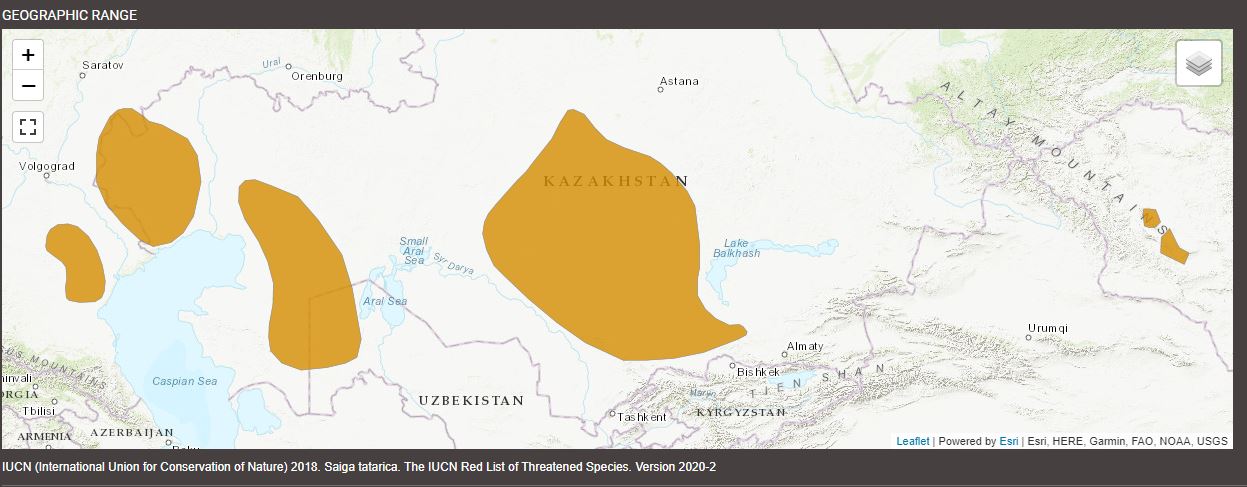

The history of Saiga antelopes in the last century has been one of cycles of decline and recovery. Saigas used to occur in the millions, but declined dramatically, almost to the point of extinction, in the early 20th century due to commercial hunting. They were subsequently protected, and populations began to rebound. However, after illegal hunting of Saigas for meat and horn became popular, numbers started to crash again from over one million in the early 1980s to around 100,000 in 2005. After intensive conservation efforts, numbers increased to just over 300,000 before the 2015 die off. Saigas occur in five different populations, three of which are in Kazakhstan and comprise the majority of the world’s Saiga population. Therefore, the 2015 mortality event, which killed approximately 80% of the Betpak-dala population in Kazakhstan, or just over 60% of the world’s population, had a significant, and potentially catastrophic, impact not only on the affected animals, but on Saigas as a species.

Map showing the world distribution of Saiga antelopes (yellow areas) – the yellow area on the right is the location of the Betpak-dala population, site of the 2015 mortality event. (Image: IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) 2018. Saiga tatarica. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2020-2)

One aspect of disease outbreaks is that they can create an extra “whammy” for a population that is already under pressure. Many wildlife populations are affected by negative impacts on their normal environment (such as habitat destruction and degradation), competition with, or predation by, other species (which are often not native to the area, i.e. introduced species) or direct human activity, such as hunting. A mass mortality event, or disease that puts further pressure on their numbers, may just be the last nail in their species’ coffin, so to say.

Some disease outbreaks can take a previously common species to the brink of extinction, without the need for other threats. An example of this is Tasmanian Devil Facial Tumour (TDFT), which is thought to have reduced Tasmanian devil numbers by about 75%, taking the species from being classified as “least concern” to “endangered” in just over a decade.

But disease-related population crashes like the one experienced by the Saiga antelope or Tasmanian devil, have significant effects beyond the obvious reduction in numbers. It also means that genetic diversity within the population is dramatically decreased due to the much smaller number of animals that are left to reproduce and pass on their DNA. In ecological terms, that is referred to as a genetic bottleneck.

These bottlenecks can have important flow-on effects, by reducing the species’ ability to adapt to a changing environment, or evolve, but also by reducing the population’s ability to respond to new disease threats, both of which may lead to further reductions in population size.

In the case of the Saiga antelopes, we don’t know yet how big an effect repeated population declines followed by rebounding population growth will have on the long term survival of the species. Luckily, it appears that the population is recovering from the latest population crash as well, with a 2019 census suggesting the population has rebounded to over 300,000 individuals, thanks to extensive conservation efforts and amazing resilience by this species.

But there are examples with far less of a happy ending, where disease has significantly decreased population size to the point of causing extinctions. Chytridiomycosis, a disease caused by a fungus, is believed to have directly contributed to the extinction of at least seven Australian frog species, and population declines of another six. Worldwide, that disease is thought to have contributed to the decline and/or extinction of over 500 amphibian species!

Green and golden bell frog – one of many Australian frog species impacted by chytridiomycosis

So if one giraffe sneezes, it would be polite to say “Gesundheit”, and make sure it has a tissue handy – after all, that rather big nose is bound to produce some rather impressive amounts of snot….. But will it matter to all of its giraffe friends? It may not, if it is a contained event and there is no significant flow-on effect to the rest of the population. But if the sneeze is the onset of a rapidly spreading disease outbreak, that will affect many giraffes and greatly reduce overall population numbers….then maybe it does. And without further investigation and keeping an eye on the health of our wildlife, it can be difficult to know which sneezes are just a little sneeze, and which ones portend the onset of a giraffe disease epidemic.

There is another reason why we shouldn’t completely ignore the sneezing giraffe. Some infectious diseases affect multiple species of animals, including livestock and pets, and sometimes also humans. The latter are referred to as zoonotic diseases. But let’s discuss this in the next post!